How We Became A Family / In the News

Let's Get Rid of Secrecy Within Donor-Conceived Families

Written By Naomi Cahn and Wendy Kramer

From movies like The Kids Are All Right and Delivery Man to the MTV reality showGeneration Cryo, donor-conceived children in fiction and real life are growing up and attempting to find out where they came from. But what about all of the kids who don’t know how they were conceived? As we write in our new book, Finding Our Families, a majority of married straight couples still don’t tell their children if they used donor eggs or sperm to get pregnant.

Secrecy has long been intimately intertwined with donor conception. Once upon a time, non-disclosure was standard. Almost no one talked about whether they had used a donor, and the donors themselves didn’t worry that their biological offspring might come knocking. This culture of secrecy meant that many parents with donor-conceived children didn’t think about disclosure, because no one ever told them that it might be the right thing to do for their children. Most children didn’t know they were donor-conceived, so they never asked questions. Sperm banks and, more recently, egg donation programs drew on traditional adoption practices and beliefs—keeping health or genetic information private, never telling the adopted that they were not the biological children of their parents. Keeping the secret was seen as protecting the entire family from stress and pain.

The adoption world moved long ago towards telling children the truth about their origins, but change has been much slower for the donor-conceived. While professional organizations now advocate disclosure, some parents still struggle with whether, when, and how to tell, and many still will not do so.

Parents have a number of reasons to worry about telling, and have told us:

Written By Naomi Cahn and Wendy Kramer

From movies like The Kids Are All Right and Delivery Man to the MTV reality showGeneration Cryo, donor-conceived children in fiction and real life are growing up and attempting to find out where they came from. But what about all of the kids who don’t know how they were conceived? As we write in our new book, Finding Our Families, a majority of married straight couples still don’t tell their children if they used donor eggs or sperm to get pregnant.

Secrecy has long been intimately intertwined with donor conception. Once upon a time, non-disclosure was standard. Almost no one talked about whether they had used a donor, and the donors themselves didn’t worry that their biological offspring might come knocking. This culture of secrecy meant that many parents with donor-conceived children didn’t think about disclosure, because no one ever told them that it might be the right thing to do for their children. Most children didn’t know they were donor-conceived, so they never asked questions. Sperm banks and, more recently, egg donation programs drew on traditional adoption practices and beliefs—keeping health or genetic information private, never telling the adopted that they were not the biological children of their parents. Keeping the secret was seen as protecting the entire family from stress and pain.

The adoption world moved long ago towards telling children the truth about their origins, but change has been much slower for the donor-conceived. While professional organizations now advocate disclosure, some parents still struggle with whether, when, and how to tell, and many still will not do so.

Parents have a number of reasons to worry about telling, and have told us:

I don’t want to confuse my child and disrupt her normal childhood. I don’t want to revisit those uncomfortable feelings of shame about infertility. If I tell my child, then I’ll have to tell family members and friends as well. I know I probably should tell, but I fear my child will become angry and reject me when she finally finds out. She might feel more connected to her genetically related parent and not to me. I don’t think my child needs to know unless the fact of her donor conception becomes important, such as for medical reasons. My partner and I disagree over whether to disclose. I worry that telling is not the end of the dialogue or the story, and that I may be unable to answer my child’s questions about her genetics or ancestry, so better not to begin the conversation at all. I don’t want my child to think that genetics are all that important.So, yes, the decision to talk about donor conception, even if you value familial honesty, can be hard. But according to a new study of egg-donor families by researchers at Weill-Cornell Medical College, early disclosure is best for the whole family. Researchers found that parents who told their children before they turned 10 reported no anxiety relating to disclosure and expressed full confidence that they had done the right thing. By contrast, among the non-disclosing families, there were high levels of anxiety as they waited for the “right time” to tell, and found themselves confronting the challenge of disclosing to teenagers or young adults. And in a systematic review of 43 studies on the disclosure decision-making process for heterosexual couples who had used donor eggs, sperm, and embryos, researchers found that the parents who disclosed emphasized children’s best interests, their rights to know that they are donor-conceived, honesty as an essential component of the parent-child relationship, and the stress inherent in keeping a secret. By contrast, while those parents who had not disclosed also emphasized the best interests of their children, they saw no benefit from disclosure and wanted to protect the child from stigma or other damage. In some families, of course, disclosure decisions are fairly easy. Donor conception is difficult to hide in single parent and LGBT families, and research shows that children in those families learn at an earlier age than do children in heterosexual families. It’s the increasing number of these non-“traditional” families that has helped bring much more openness to the donor conception process. As we write in our book, not telling your child does not render the fact of the conception irrelevant. Reminders about donor conception will frequently come up, perhaps as you or others try to figure out why your child is so tall, or so good at math, or so outgoing. When your pediatrician asks about your child’s medical history, you will have to lie. You may feel uncomfortable when friends talk easily about how much their children look like them, or when they share with you their struggles on how to explain to their children how Daddy planted that seed in Mommy’s belly. This secrecy around donor conception is a heavy load to carry, and the layers of deception build up. The best-kept secret can warp family life, filling children with anxiety they don’t understand, and parents with guilt. In an effort to protect kids they love from what parents perceive as the difficult truth of their origins, parents are hurting them—and the parent-child bond—instead. Naomi Cahn is the Harold H. Greene Professor at George Washington University Law School. Wendy Kramer is the co-founder and director of the Donor Sibling Registry. Original story published on Slate.com

The Unregulated Sperm Donor Industry

illustration by Monica Ramos

illustration by Monica Ramos

By RENE ALMELING

NEW HAVEN — The new movie “Delivery Man” stars Vince Vaughn as a former sperm donor who finds out that he has more than 500 children. Is this a Hollywood exaggeration or a possible outcome? Truth is, no one knows. In the United States, we do not track how many sperm donors there are, how often they donate, or how many children are born from the donations.

Unlike a Hollywood happy ending, however, this lack of regulation has real consequences for sperm donors and the children they help produce. The Journal of the American Medical Association published one case study of a healthy 23-year-old donor who transmitted a genetic heart condition that affected at least eight of 22 offspring from his donated sperm, including a toddler who died from heart failure. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine recommends genetic screening of sperm donors, and many banks do it, but the government does not require it. The risks become magnified the greater the number of children conceived from each donor.

How did we get to this point? Sperm donation has evolved from a practice of customized production to an industry that resembles mass manufacturing.

One of the first uses of donated sperm was reported in 1909 by a doctor recalling his days as a student observing medical practice. A 41-year-old wealthy merchant and his wife had been unable to conceive. An examination revealed that the husband did not produce sperm. The doctor requested a sperm sample from the “best-looking member of the class.” He asked the wife to come in for an examination, administered chloroform, and without her knowledge, inseminated her with the student’s sample. Nine months later, she gave birth to a healthy boy.

Several aspects of this vignette foreshadow the trajectory of sperm donation (but not the practice of inseminating women without their knowledge). The medical profession continued to play a central role. Doctors selected donors on the basis of their “superior” qualities, secrecy marked the enterprise, and sperm was produced for a particular recipient. According to one mid-century study of several hundred men, the majority of donors produced less than 10 samples.

AIDS changed everything. As doctors in the 1980s learned how the disease was transmitted, it was no longer advisable to transfer fresh samples directly from donor to recipient. Physicians began to use frozen sperm from commercial banks because it could be quarantined for six months, after which the donor could be retested for H.I.V.

Under these conditions, mass manufacturing began to make sense. A sperm program required personnel to keep track of donors, lab technicians to test samples, facilities to store the frozen vials, and distribution departments to ship the product around the world. Doctors could not handle these complexities on their own, so the procurement of sperm was outsourced to for-profit banks.

Today, the supply of sperm in the United States is concentrated in a few large companies that maintain multiple offices around the country, generally near college campuses. Recruiters write cheeky advertisements (“Get paid for what you’re already doing!”). They comb through hundreds of applicants to find the “few good men” who will pass rigorous medical screening and have sperm counts high enough to survive cryogenic freezing. Because of the large investment in finding donors, sperm banks require men to make regular deposits for months on end, resulting in large caches of genetic material that can produce tens and perhaps even hundreds of offspring.

Regulation has not kept up with the fundamental shift in how the fertility industry sources sperm. No federal agency or professional organization monitors the number of men donating, vials sold, or children conceived. The Food and Drug Administration requires that sperm banks test donors for particular diseases, but does not collect data about how many times men donate. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conduct an annual survey of fertility clinics, but don’t ask about sperm donation. Sperm banks say they cap the number of offspring per donor, but have no way of compelling customers to report when they get pregnant or give birth.

Similar information gaps about the number of donors, and the number of children born, plague egg donation. But until now, the market for eggs has resembled the old-fashioned version of sperm donation: women produce a small number of fresh eggs for a particular customer. Now that scientists have figured out how to successfully freeze eggs, egg banks are being established, and the scale of production may eventually lead to the same challenges sperm banks face.

We owe it to sperm donors and the children born from their donations to gather basic data. Sperm banks should be required to report the number of vials sold per donor to the F.D.A. The C.D.C. should expand its survey to include sperm donation. These reasonable first steps would allow for an evidence-based discussion about whether there should be regulations to limit the number of offspring per donor. At the least, we would get a handle on whether the typical number is in the dozens or hundreds.

Read With Your Children, Not to Them

Research has found that reading with young children and engaging them can make a positive impact on the child's future and their family. Bradford Wiles is an Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist in early childhood development at Kansas State University. For most of his career, Wiles' research has focused around building resilience in vulnerable families. His current research is focused on emergent literacy and the effect of parents reading with their children ages 3 to 5 years old.

"Children start learning to read long before they can ever say words or form sentences," said Wiles. "

My focus is on helping parents read with their children and extending what happens when you read with them and they become engaged in the story." The developmental process, known as emergent literacy, begins at birth and continues through the preschool and kindergarten years. This time in children's lives is critical for learning important pre-literacy skills. Although his research mainly focuses on 3-5 year olds, Wiles encourages anyone with young children to read with them as a family at anytime during the day, not just before going to bed. He also believes that it is okay to read one book over and over again, because the child can learn new things every time.

"There are always opportunities for you both to learn," said Wiles, "and it creates a family connection.

Learning is unbelievably powerful in early childhood development." It goes deeper than just reading to them, as parents are encouraged to read with their children. Engaging children is how they become active in the story and build literacy skills. "There is nothing more powerful than your voice, your tone, and the way you say the words," said Wiles. "When I was a child, my dad read to me and while that was helpful and I enjoyed it, what we are finding is that when parents read with their children instead of to them, the children are becoming more engaged and excited to read." Engaging the child means figuring out what the child is thinking and getting them to think beyond the words written on the page.

While reading with them, anticipate what children are thinking. Then ask questions, offer instruction, provide examples and give them some feedback about what they are thinking.

"One of the things that I really hope for, and have found, is that these things spill over into other areas," said Wiles. "So you start out reading, asking open-ended questions, offering instruction and explaining when all of the sudden you aren't reading at all and they start to recognize those things they have seen in the books. And that's really powerful."

Wiles explains it in a scenario where a mother reads a book with her 4 year old about a garden. Then they go to the supermarket and the 4 year old is pointing and saying, "look there's a zucchini." The child cannot read the sign that says zucchini but knows what that is because they read the book about gardens.

During this time called the nominal stage, the developmental stage where children are naming things, a child's vocabulary can jump from a few hundred words to a few thousand words. The more exposure they've had through books and print materials, the more they can name things and understand.

It's the emergent literacy skills that can set the stage for other elements. The school of Family Studies and Human Services at Kansas State University is producing lesson plans to help families learn how to read with young children. These lesson plans are research-based but they have been condensed into usable and applicable lessons for families. Source" Kansas State University Research and Extension (2013, September 12). Read with your children, not to them. ScienceDaily. Retrieved November

Actress Elisabeth Röhm Shares Her Infertility Story

from RESOLVE.org

Listen to the great interview actress, author, and activist Elisabeth Röhm had with RESOLVE’s President/CEO Barbara Collura. The “Law & Order” actress and author of Baby Steps: Having the Child I Always Wanted (Just Not As I Expected) discusses her family building journey and why she is a vocal advocate for the infertility community. Listen now.

from RESOLVE.org

Listen to the great interview actress, author, and activist Elisabeth Röhm had with RESOLVE’s President/CEO Barbara Collura. The “Law & Order” actress and author of Baby Steps: Having the Child I Always Wanted (Just Not As I Expected) discusses her family building journey and why she is a vocal advocate for the infertility community. Listen now.

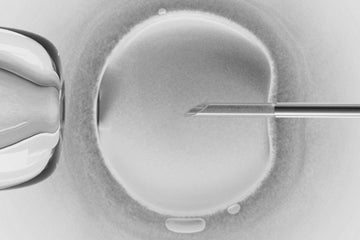

IVF Linked to Slightly Higher Rate of Mental Retardation